The post-war order of Syria: A country torn between ethnical division and geopolitical interest

As the fighting against ISIS draws to a close in its strongholds of Mosul and Raqqa the factions of the Syrian War and their international backers are laying the groundwork for a new post war territorial order of the Syrian political landscape.

As the fighting against ISIS draws to a close in its strongholds of Mosul and Raqqa the factions of the Syrian War and their international backers are laying the groundwork for a new post war territorial order of the Syrian political landscape. Since the start of the uprising the country has been ravaged, its population brutalised and the societal fabric burned, yet it appears that after almost 6 years of disastrous fighting, the hot phase of the war might come to an end, and a new, more stable power constellation emerges.[i]

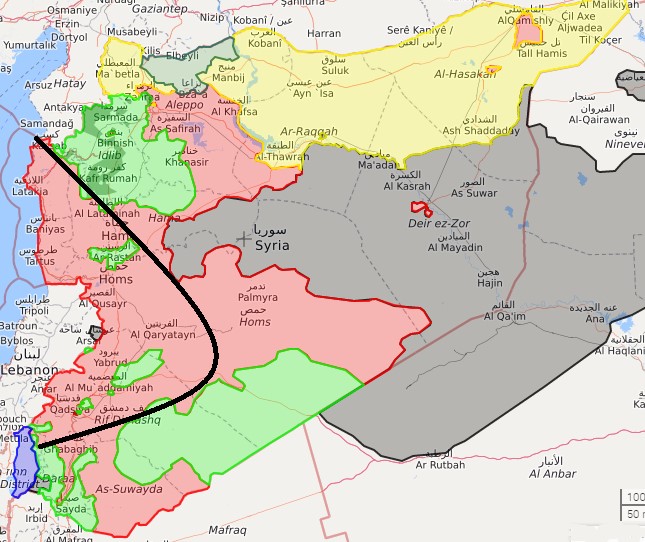

Starting at least in late 2013, the Assad regime had begun to strategically abandon parts of the country it could no longer hold, and as with the Kurdish YPG, even peacefully given up control of whole regions in the east. It became clear, that what the government strived for was control over a rump state, stretching from Damascus along the strategic highway passing Hama and Homs up to the Alawite homeland along the Mediterranean coast (marked by the black crescent) [ii]. In line with this doctrine, small enclaves of rebels inside this area were besieged, starved and ultimately expelled to rebel held territory, mostly in Idlib. This practice, first employed in early 2015, oftentimes included the removal of the entire Sunni population of strategic towns and its replacement with Shia refugees from Syria, Lebanon and Iraq, as happened with the swap of residents from Zabadania for those from Fuaa and Kefraya.[iii] It has been alleged, that such ethnic cleansings are part of a larger, Iranian backed, strategy, to create areas of exclusive sectarian control between Damascus and the coast, but also along the mountainous borders of Lebanon.[iv]

The continuous relocation of Sunnis to rebel held territory offers a glimpse at the long term strategy of Damascus and Teheran. As these areas in the north and south are by now filled with rebel forces and easily supplied from Jordan or Turkey, it might not be in Assad’s best interest to conquer them in the foreseeable future. It appears that instead, the Syrian Arab Army and its extensive sectarian militias have now embarked on a larger offensive against the Islamic State in the East, in order to lift the siege of Deir-az-Zor and regain the surrounding oil and gas fields.

Kurdish Autonomy

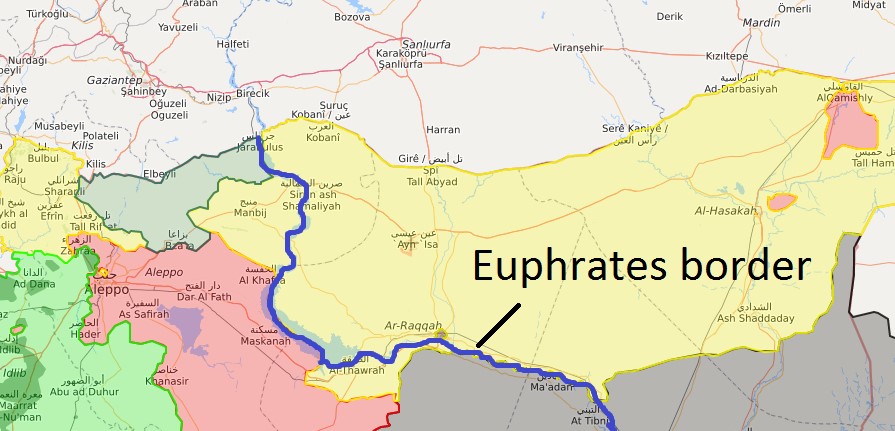

At the same time the Syrian Defence Forces, mostly Kurdish YPG with links to the PKK, has been sufficiently supplied by the US to move out of Syria’s Kurdish areas and push ISIS back on every front. Even though the SDF was able to conquer and hold areas on the southern side of the Euphrates River, it appears that this natural obstacle might become the border between a quasi-autonomous Kurdish state in Syria, much like its counterpart in Iraq. This predictions is supported by the fact that on June 18tha Syrian airplane bombing the SDF was shot down by the US Airforce, and the Kremlin merely responded that henceforth all US planes west of the Euphrates will be considered hostile, thus establishing a de facto partition line. [v]

In the coming months the SDF will finish its conquest of Raqqa and possibly push further south along the Euphrates, extending its control into ISIS areas. To appease the newly conquered Arab populations, the SDF integrated some FSA linked Arab rebel groups into its ranks[vi] and plans to establish a municipal government consisting mostly of Arabs, but also Kurds and Turkmen.[vii]It thus appears, that the SDF has come to stay and if its ideals of democratic self-governance are carefully executed might establish a durable autonomy east of the Euphrates, short of outright declaring independence. This Kurdish power relies on a fragile balance of US and Russian protection however, as the Damocles sword of a Turkish invasion of Norther Syria constantly looms over it, as the situation in the canton of Afrin demonstrates.

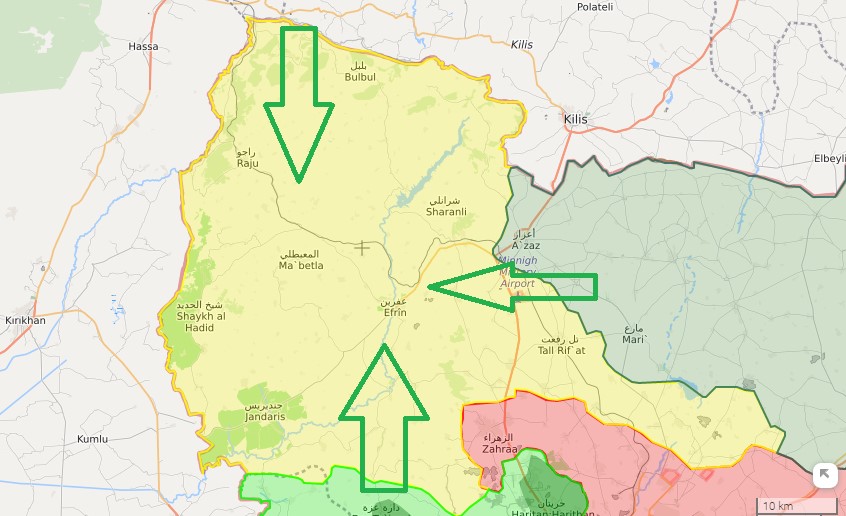

The Afrin corridor

According to unconfirmed reports[viii], the Turkish Army is massing at its southern border for an Operation named “Euphrates Sword” (its last operation to liberate Al-Bab was labelled “Euphrates Shield”). An attack on the Kurdish enclave of Afrin would open a corridor inside Syria between the Turkish held territories around al-Bab and the rebels in Idlib. While such a move would weaken the YPG and destroy their aspirations to connect the canton to its territories east of the Euphrates, it would certainly escalate tension with Russia and the US, who are both reported to recently have stationed small contingents of Special Forces in Afrin[ix][x] to deter a possible attack.

With a bellicose president at the helm of the Turkish Armed Forces however, an intervention is likely, possible using only local rebel forces in order to provide plausible deniability to Ankara. If a local agreement can be reached with Russia or the US, the isolated enclave could be quickly integrated in a larger, Turkish dominated buffer-zone in the north of Syria. Recent unconfirmed reports of Kurdish officials suggest that the Russian government is pressuring the Kurdish canton of Afrin to either allow Syrian government troops into their territory, or face the invasion of Turkish troops alone.[xi]

The South

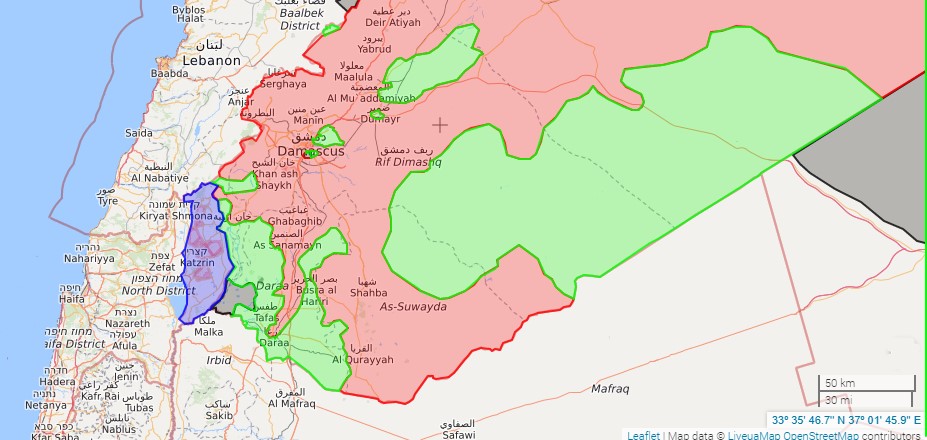

Uncertainty prevails concerning the future of Syria’s southern rebel enclaves, since they have been unable to conquer neither large continuous swaths of land nor a major city, and their holdings in the desert border region might appear impressive, but provide little defence against an armoured offensive with air support.

Operations of the SAA against ISIS have brought them to the Iraqi border and cut of any possible advance route for the FSA into ISIS held eastern Syria.[xii] Even though US Special Forces are present, and the “Southern Front Alliance” is supplied and trained by the US (according to unconfirmed reports[xiii][xiv]), their position appears too weak to hold out against any prolonged offensive of Syrian, Iranian and Russian forces. If the current trend of population exchanges continues however, a possible solution would be a swap the besieged rebel territories in Ghouta, close to Damascus, and elswhere for the government held parts of the Daraa Governorate, resulting in a stable, quasi-autonomous and foreign (Saudi, Jordanian and US) backed province, similar to Idlib in the North. This would also facilitate the eradication of an ISIS enclave that started to establish itself along the Golan border with Israel.

The final picture

Any prediction about the future of Syria’s volatile civil war will be oversimplified and prone to the danger of simply extending current trends, and so is this short article. However it might help to understand future conflict lines and options to avoid confrontations. If the trends that have been discussed in this article are thought through, one might end up with such a unidimensional map of the future political landscape of Syria.

The outlined areas do not show independent entities, but rather de-facto autonomous zones, similar to areas such as the Donetsk and Luhansk Republics in eastern Ukraine, or Nagorno-Karabagh in Azerbaidjan. In this scenario, both Iranian and Russian ambitions would be satisfied, as Assad’s rule would be sufficiently secure, for the Russian military to safely operate their only Mediterranean naval base in Tartus and the airfield near Latakia, while simultaneously providing Iran with a “Shia-arch” via Iraq to supply Hezbollah in Lebanon. The Syrian regime would however stay weakened and in need of support by the two powers. Turkey’s interests could be safeguarded by providing them with an influence zone in northern Syria, curbing Kurdish aspirations for independence and possibly settling Sunni refugee populations. The US, Saudi Arabia and their allies who currently support moderate rebel groups in the south could save face by establishing democratic self-rule the Daraa governorate, while the SDF would gain an autonomy status similar to their kinsmen in Iraq, protected by an US-enforced no-fly zone east of the Euphrates. Additionally to it being an entertaining exercise, outlining and drawing a Syria after the gruesome war might help to find a workable solution and visualise a possible compromise of the diverse powers invested in the war.

[i] SAA in red, FSA/moderate rebels in light green(with Al-Qaida linked rebels in shaded areas), Turkish backed rebels in dark green, YPG/SDF in yellow and ISIS in black. (all maps are taken from http://syria.liveuamap.com/)

[ii] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/04/syria-approaching-de-facto-partition-amid-assad-military-setbacks

[iii]http://syrianobserver.com/EN/Commentary/29693/Opinion_Is_Zabadani_Land_Swap_Prelude_Partitioning_Syria

[iv] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jan/13/irans-syria-project-pushing-population-shifts-to-increase-influence

[v] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-4617896/Russia-vows-shoot-flying-objects-Syria.html

[vi] http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-mideast-crisis-syria-jarba-idUKKBN15G51W

[vii] http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/syriasource/the-ramifications-of-the-sdf-governance-plan-for-raqqa-post-isis

[viii] https://twitter.com/sayed_ridha

[ix] https://www.almasdarnews.com/article/russian-troops-deployed-afrin-turkey-prepares-massive-assault/

[x] http://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/270620175

[xi] http://syria.liveuamap.com/en/2017/5-july-former-kurdish-official-russia-threatening-pyd-to

[xii] https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2017-06-12/fighting-for-syrias-daraa-intensifies

[xiii] Ghattas, Kim (9 December 2014). “Syria war: Southern rebels see US as key to success”. BBC News. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

[xiv] Haid, Haid (21 August 2015). “The Southern Front: allies without a strategy”. Heinrich Böll Foundation. Retrieved 30 August 2015.